THE MORE THE MERRIER: LENORA MATTINGLY WEBER’S BEANY MALONE NOVELS

When the internet was new I did all the things everyone did with it, got hooked, sold my soul to eBay, downloaded enough porn to make a string of flesh all around the world, located all my old high school classmates and found myself an internet boyfriend in the former Soviet Union. I reached out to every conceivable friend and lengthened my penis. And then on Google I typed in the words “Lenora Mattingly Weber” to see what would pop up. No, this was before Google, there must have been another, primitive search engine. That’s when I found out there were other people just like me, only most of them were women. We were all secret readers of a forgotten YA writer and each of us thought we were the only person in the world.

My sister and I read these books when we were kids, and really never stopped, even though Weber herself died in January 1971 and a year later the books stopped coming. She had written lots and lots of books, and they are the kind you don’t mind reading and re-reading, which we did for years. Even as an adult, from time to time I’d see an old copy of one of the Weber books on a thrift store shelf, or spot a pastel cover in a box of books on a gravel bed at the flea market. And I remember, maybe 20 years ago, before the internet made all this unnecessary, hiring one of those “book search” places, a firm in Berkeley that was able to locate all the copies of Weber I wanted for really absurdly low prices. The market had dropped out, no one wanted them any more, I guess. I even got an autographed copy and could trace Weber’s spiky, up and down handwriting with my own fingertip. And my sister kept all these books in New Jersey and would mail them to me when I needed a fix.

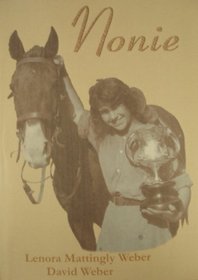

Weber’s career was more tangled than either of us realized. In recent years, her eldest son David has edited his mother’s autobiographical writings and added on his own account of her life after the unfinished memoir trails off. The resulting volume, Nonie (Image Cascade), has a little bit of fish and a little bit of fowl, but we treasure it for its glimpse into Weber’s life, unmediated by the distance of fiction. From it we learn what we had somehow suspected, that being a woman writer in the US mid-century probably could never have been easy even if you were rich, and it’s even worse when you’re not rich and have six kids and a husband who, well maybe I’m being unkind, seems like a millstone around her neck. As a girl she had adored Al Weber, the basketball coach at her high school, and looked up to him in every way, but then within months after their marriage he had a kidney stone removal that left him in disability the rest of his life, so all he could really do was lie supine on the back porch and complain.

Weber began her writing career as a way to make money, but she hit a motherlode of memories and feelings that animate her best books even now, 80 years after she began. She wrote story after story for the big slicks of the day, The Saturday Evening Post, Ladies Home Journal, Redbook, Cosmopolitan, but for her fans she hit her stride when she published Meet the Malones in 1943. In essence MTM is a homefront story, rather like David Selznick’s contemporary epic film Since You Went Away; while the nation waged World War II, its artists must often have tried to enunciate what it was about the USA that made it worth fighting for, and so there was an intense, sometimes pathological focus on the problems of home and family, exacerbated by the forced absence of so many and the inevitable tensions engendered when everyone is working as hard as they can for a common victory. The Malones—well, you could tell from the title it wasn’t going to be a story of Newport upper crust white breads—these were sort of a scrappy, take them as they are family from, of all places, Denver, a city which I know almost entirely from Weber’s novels. I know it so well that I have the feeling that if you blindfolded me and set me down in the middle of an intersection, I could make my way pretty well to the ramshackle, warm welcoming house the Malones lived in.

The mother was dead. The father was a newspaper columnist for the Denver Post—“our on again off again gone again father,” the children dubbed him. There were four children, one of whom—the homecoming princess, Elizabeth—had married a GI; the others were in high school or junior high. Johnny Malone was a would be writer and historian whose researches often led him into recherche areas of early Colorado history, which I snapped up like breadcrumbs thrown at a flock of pigeons. Johnny was one of those absent minded professor types, and it was pretty much up to his younger sisters, Mary Fred and Beany, to keep him fed and taken care of. Yes, Mary Fred and Beany—might as well get those names out right away, for they are the biggest shame any Weber fan has to swallow. And yet, after a few years, you too will be defiant and wearing your button, “Beany Malone,” with pride. Even though Meet the Malones did a fair job of developing dramatic storylines for all four children, you could tell it was the youngest, Beany, who was closest to her heart, and when the book’s success made her publisher ask her to consider a sequel, Weber returned five years later with Beany Malone (1948), a very different sort of book, postwar in its feeling, more highly developed in its moods and imagery, but recognizably the same teenage girl and the same family and, sort of, the same USA. Here she secured an intradiegetical superiority to her entire family, and I think kids liked that, they liked seeing the youngest become the prism through which the cumbersome family (and social) structure could be glimpsed. All in all there were to be 14 Beany books, and the first ten are, for me, the high water mark of a certain kind of American writing in the 20th century. (The final four are marred by what I consider a disastrous plot development in the lives of the Malones, but that’s not to say that they’re without virtue.) (Indeed some fans actually prefer the final four—I wonder what you will make of them, when you wind up reading the whole series.)

Though the decades changed behind her like cloth backdrops, Beany herself never really changed all that much, and it takes her eleven books to get herself through high school. The pains and pleasures of high school are what she learns; things never get as bad for her in school as they do, say, in Young Torless or Spring Awakening, but once she got going Weber was incapable of a false emotional note, and her heroine’s boyfriend and dress problems seem every bit as compelling as do her occasional grapplings with Cold War conservatism, social hypocrisy, sexual rebellion, the nomadism at the heart of American life. People just don’t stay settled down; just when you come to care for them deeply, they’re gone. And contrariwise from out of the past those you thought you had lost come back, sometimes strangely and scarily altered and moody. Reading Nonie, we get a picture of Lenora Weber trying desperately to see to the welfare of her entire farflung family and sometimes it just seems like too much; then again one measures this domestic sphere against the great accomplishment of her 32 novels and I wonder, she must in some ways have been rather absent herself, from the family from whom she took so much material.

I think I’m the only guy in the group, though some may be lurking. Maybe 7 or 8 years ago some of the women on the list who lived near each other in Michigan or somewhere got together and had a grand old time discussing details of the Weber books and other odds and ends of life. They decided to try to go bigger next time and have a national convention as it were. I started becoming interested in going the year that the group met in Denver. I was in Naropa later that summer so I couldn’t afford to hit Colorado twice in one month, but oh how I longed to be there! For one thing, all of Weber’s personal papers are kept in the special collections of the Denver Public Library, and our group got to go in and look around! Apparently there is a version of the final Beany Malone novel Come Back Wherever You Are that is very different than the one that finally hit the stands—a much more despairing and cruder, more passionate book. Those lucky women got to see it, touch it, copy it!

And they went around to the “originals” for all the sites in the Weber books—the church Beany married in, the high school she attended, the soda shop, the country club, the teen center. One of Weber’s granddaughters still lives in Denver, and met the group and showed them around and invited them in to see her collection of her grandmother’s memorabilia. There’s even a picture of the young Lenora Weber interviewing Mae West back in the 1930s at the Denver Press Club.

Every year the group goes on a summer retreat, and it doesn’t have to be Denver; maybe some other American city with an incidental link to Beany Malone’s life and times. I went to Portland to meet all of these fellow fans and had the time of my life. You know how on the internet, you can become fast friends with a bunch of people you don’t actually know—and sometimes, when you meet in the flesh, it falls flat? Not here. Perhaps we operate according to the teenage rules of friendship—the merest drop of pure sympathy, and you’re in it deep, and you’re in it forever.

—At 14 the first LPs Kevin Killian bought with his own money (spring, 1967) were the Rolling Stones, Between the Buttons, and Bobbie Gentry, Ode to Billie Joe. Today he is a San Francisco-based writer whose latest collection of stories is Impossible Princess (City Lights Books).