“Oh, what questionings of fate, and freedom, and how evil came, and what death is, and what the life to come, passed to and fro among these girls!”

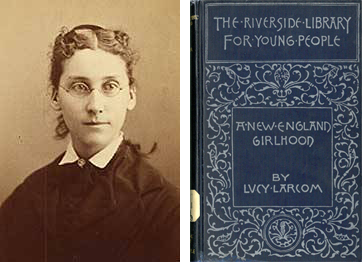

– From Lucy Larcom’s 1889 Memoir A New England Girlhood. Photo via yesteryearsnews.com.

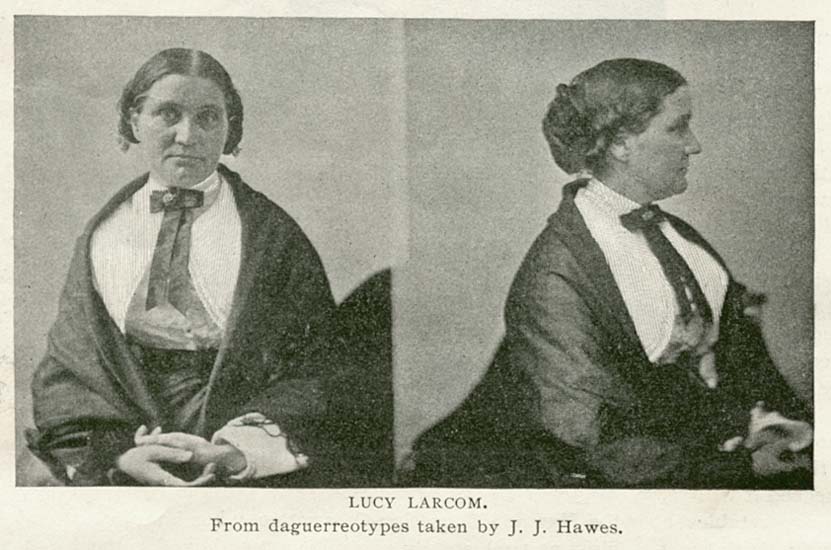

American author and poet Lucy Larcom (1824 – 1893)

Lucy Larcom was born of good standing to a pious family in Beverly, Massachusetts. She was the ninth of ten children. After her father’s death, Lucy’s mother relocated the family to Lowell where Lucy (age 11) and her sister went to work at the mills. The Larcom sisters made a huge impact at the Lowell Mills. They started a literary paper where Lucy wrote and published songs, poems, and letters. Her work even earned the respect of famous poet and abolitionist John Greenleaf Whittier. Larcom’s writings were a catalyst for change in women’s lives. She became known not only as a voice of youth labor, but as an abolitionist and suffragette. Lucy died in Boston in 1893.

Excerpted below are passages from her books, poems and publications.

After his death [Father], my mother’s thoughts naturally followed the direction his had taken; and seeing no other opening for herself, she sold her small estate, and moved to Lowell, with the intention of taking a corporation-house for mill-girl boarders. Some of the family objected, for the Old World traditions about factory life were anything but attractive; and they were current in New England until the experiment at Lowell had shown that independent and intelligent workers invariably give their own character to their occupation. My mother had visited Lowell, and she was willing and glad, knowing all about the place, to make it our home.

Above: Boot Mills, Lowell; The boardinghouses of the Merrimack Manufacturing Company; Cotton mill, early 1910s (photograph by Lewis W. Hine)

It was not in my mother’s nature closely to calculate costs, and in this way there came to be a continually increasing leak in the family purse. The older members of the family did everything they could, but it was not enough. I heard it said one day, in a distressed tone, “The children will have to leave school and go into the mill.”

Above: “A Lowell Mill Girl” from The Lowell Daily Sun, June 2, 1894; Photo by Lewis W. Hine

Above: Photo by Lewis W. Hine via Clemson.

For the first time, our young women had come forth from their home retirement in a throng, each with her own individual purpose. They had come to work with their hands, but they could not hinder the working of their minds also.

I defied the machinery to make me its slave. Its incessant discords could not drown the music of my thoughts if I would let them fly high enough.

I weave, and weave, the livelong day:

The wood is strong, the warp is good:

I weave, to be my mother’s stay;

I weave, to win my daily food:

But ever as I weave,” saith she,

The world of women haunteth me.

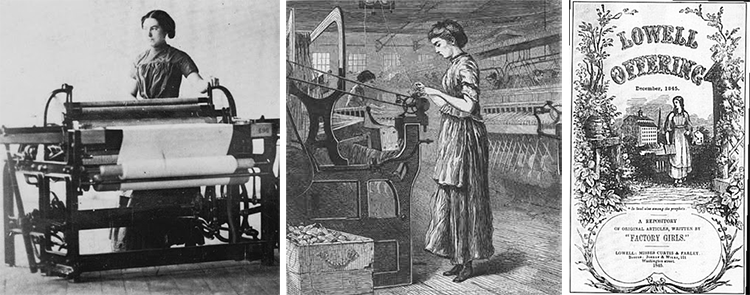

Above: A Lowell Mill Girl Spinning Fabric; Illustration from the Lowell Offering; cover of the Lowell Offering, “A Repository of Articles, written by FACTORY GIRLS.”

The carding room, with its great groaning wheels,

Its earthquake rumblings, and its mingled smells

Of oily suffocation;

Long clean alleys, where the spinners paced

Silently up and down, and pieced their threads,

The spindles buzzing like then thousand bees.

The Long threads were wound from beam to beam,

And glazed, and then fanned dry in breathless heat.

Here lithe forms reached across wide webs, or stooped

To disentangle broken threads, or climbed

To where their countenances glistened pale

Among swift belts and pulleys.

The door, swung in on iron hinges, showed

A hundred girls who hurried to and fro,

With hands and eyes following the shuttle’s flight,

Threading it, watching for the scarlet mark

That came up in the web, to show how fast

Their work was speeding. Clatter went the looms,

Click-clack the shuttles. Gossamer motes

Thickened the sunbeams into golden bars,

And in a misty maze those girlish forms,

Arms, hands, and heads, moved with the moving looms,

That closed them in as if all were one shape,

One motion.

My sister Emilie became acquainted with a family of bright girls, near neighbors of ours, who proposed that we should join with them, and form a little society for writing and discussion, to meet fortnightly at their house. [We] named ourselves “The Improvement Circle.” If I remember rightly, my sister was our first president. The older ones talked and wrote on many subjects quite above me. I was shrinkingly bashful, as half-grown girls usually are, but I wrote my little essays and read them, and listened to the rest, and enjoyed it all exceedingly. Out of this little “Improvement Circle” grew the larger one whence issued the “Lowell Offering,” a year or two later.

When a Philadelphia paper copied one of my little poems, suggesting some verbal improvements, and predicting recognition for me in the future, I felt for the first time that there might be such a thing as public opinion worth caring for, in addition to doing one’s best for its own sake.

Above: Adrienne Pagnette, an Adolescent French Girl in a Winchendon, MA mill by Lewis W. Hine

It was an event to me, and to my immediate friends among the mill-girls, when the poet Whittier came to Lowell to stay awhile. When we assembled at the “Improvement Circle,” he was there. Mr. Whittier’s visit to Lowell had some political bearing upon the antislavery cause. If the vote of the mill-girls had been taken, it would doubtless have been unanimous on the antislavery side. But those were also the days when a woman was not expected to give, or even to have, an opinion on subjects of public interest.

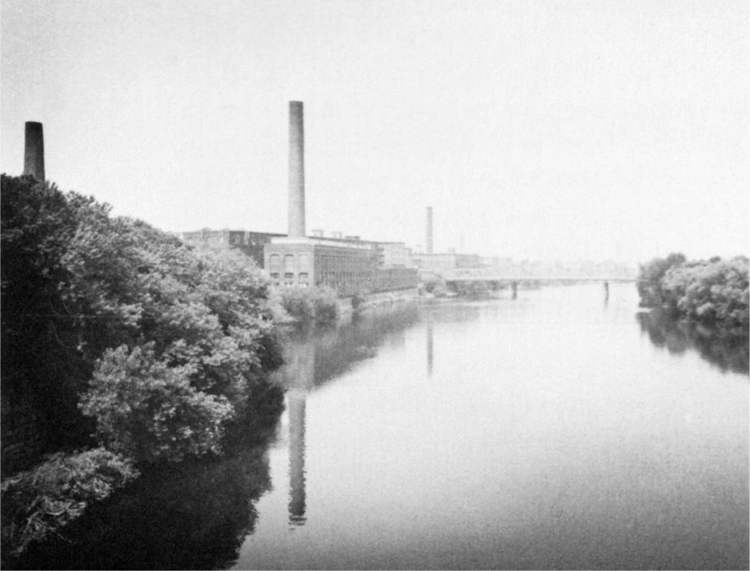

Above: The “Mile of Mills” in Lowell

We learned no theories about “the dignity of labor,” but we were taught to work almost as if it were a religion; to keep at work, expecting nothing else. It was our inheritance, banded down from the outcasts of Eden. And for us, as for them, there was a blessing hidden in the curse. I am glad that I grew up under these wholesome Puritanic influences, as glad as I am that I was born a New Englander; and I surely should have chosen New England for my birthplace before any region under the sun.